Introduction

Osteoporosis is a chronic condition that extends far beyond the natural progression of aging, affecting millions of people globally.1,2 Characterized by reduced bone density and microarchitectural deterioration, it significantly increases the risk of fractures, with the spine being particularly prone to injury.3 Among the various complications associated with osteoporosis, vertebral fractures are both the most common and the most impactful, causing chronic pain, deformity, reduced mobility and even greater mortality risk.1,3 While osteoporosis is more common in postmenopausal women due to hormonal changes accelerating bone loss, its incidence in men is rising with aging populations.3,4 Notably, age and gender remain key factors contributing to the progressive weakening of bone structure.

Despite its global burden, osteoporosis is often underrecognized. Many individuals fail to associate fractures with underlying bone deterioration, instead attributing them to ‘bad luck’ or simply ‘accidents’. This misconception delays treatment, increases the likelihood of recurrent fractures and places additional strain on healthcare systems.1 Left untreated, osteoporosis can lead to severe issues beyond vertebral fragility fractures. Chronic back pain, height loss and hyperkyphosis are common repercussions, with kyphosis potentially causing secondary complications such as abdominal bulging, breathing difficulties and gastrointestinal problems.4 Psychological effects, including depression and reduced quality of life, further underscore the importance of early detection and management. Additionally, studies report higher mortality rates in men following fragility fractures, emphasizing the need for awareness across all demographics.5

Early detection is critical, particularly for individuals over 50 years, those with a history of fractures and individuals with a strong family history of hip or vertebral fractures.5 While osteoporosis cannot be entirely prevented due to aging and genetic factors, strategies to mitigate fracture risk are highly effective.5 These include maintaining a calcium- and vitamin D-rich diet, engaging in weight-bearing activities, avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol intake.5

This review examines osteoporosis-related fractures, with a focus on their impact on the spine and pelvis. It explores advancements in diagnostic tools, evaluates current treatment strategies and underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to managing osteoporosis. By addressing these aspects, this review aims to enhance understanding, improve management practices and promote better outcomes for individuals at risk of osteoporotic fractures.

Diagnostic approaches to identify osteoporosis

Differentiating between the types of fractures associated with osteoporosis is essential for accurate diagnosis and management.6 Osteoporosis-related fractures refer broadly to any fracture that occurs in individuals with compromised bone quality, regardless of whether the injury results from low- or high-energy trauma. Among these, fragility fractures stand out as a clinically significant subset. Fragility fractures occur after minimal trauma, such as falls from a standing height, and directly indicate marked skeletal weakness. Because of their strong association with low bone mineral density (BMD), fragility fractures are often used as a diagnostic marker for osteoporosis.6,7

In contrast, fatigue fractures typically arise in bone that is otherwise healthy and subjected to excessive or abnormal repetitive loading.8 However, individuals with osteoporosis are also susceptible to fatigue fractures, as their weakened bone structure may lower the threshold for such injuries.8

Osteoporosis diagnosis requires a comprehensive approach that integrates clinical evaluations, advanced imaging techniques, and risk assessment tools.7 A common initial indication of osteoporosis is the occurrence of a clinical vertebral or femoral fracture, which highlights underlying bone fragility and necessitates further investigation.7

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is the cornerstone diagnostic tool, measuring BMD at key sites such as the lumbar spine and hip.7 A BMD T-score of -2.5 or lower confirms osteoporosis, indicating a significant deviation from peak bone density levels.7,9 DEXA is also valuable for monitoring, with regular screenings for high-risk groups reducing fracture rates by over 50%4,10 However, DEXA has limitations. For instance, lumbar DEXA may overestimate bone density due to sclerotic changes in the posterior elements, such as osteophytes or degenerative changes, potentially leading to underdiagnosis of osteoporosis in some cases.11 This limitation underscores the importance of interpreting DEXA results in conjunction with clinical findings and other diagnostic tools.11

Recent advancements in DEXA technology, including vertebral fracture analysis (VFA), have further enhanced diagnostic accuracy.4,12 VFA allows healthcare providers to detect previously unnoticed vertebral fractures, which are often asymptomatic but critically affect future fracture risk and management strategies.12 Improved imaging capabilities have revealed cases where subtle fractures were missed in earlier screenings, significantly influencing patient outcomes. For individuals over 50 years of age who have sustained fractures, diagnostic evaluations should include DEXA with VFA to comprehensively assess bone health and fracture risk.

Beyond imaging, the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool complements osteoporosis diagnostics by providing a more individualized risk assessment.4,13 FRAX combines BMD with clinical risk factors, such as age, sex, family history of fractures, and lifestyle factors, to predict a person’s likelihood of sustaining a fracture within the next decade.4,7,13 This tool is particularly valuable for enhancing the quality of prevention and treatment strategies. For example, FRAX can guide clinicians in determining whether pharmacological intervention is warranted for individual patients, even in cases where BMD alone does not meet the diagnostic threshold for osteoporosis.14 Evidence suggests that using FRAX in conjunction with DEXA improves the accuracy of fracture risk prediction and facilitates more targeted therapeutic decisions.15

Insights into anabolic and antiresorptive therapies for osteoporosis

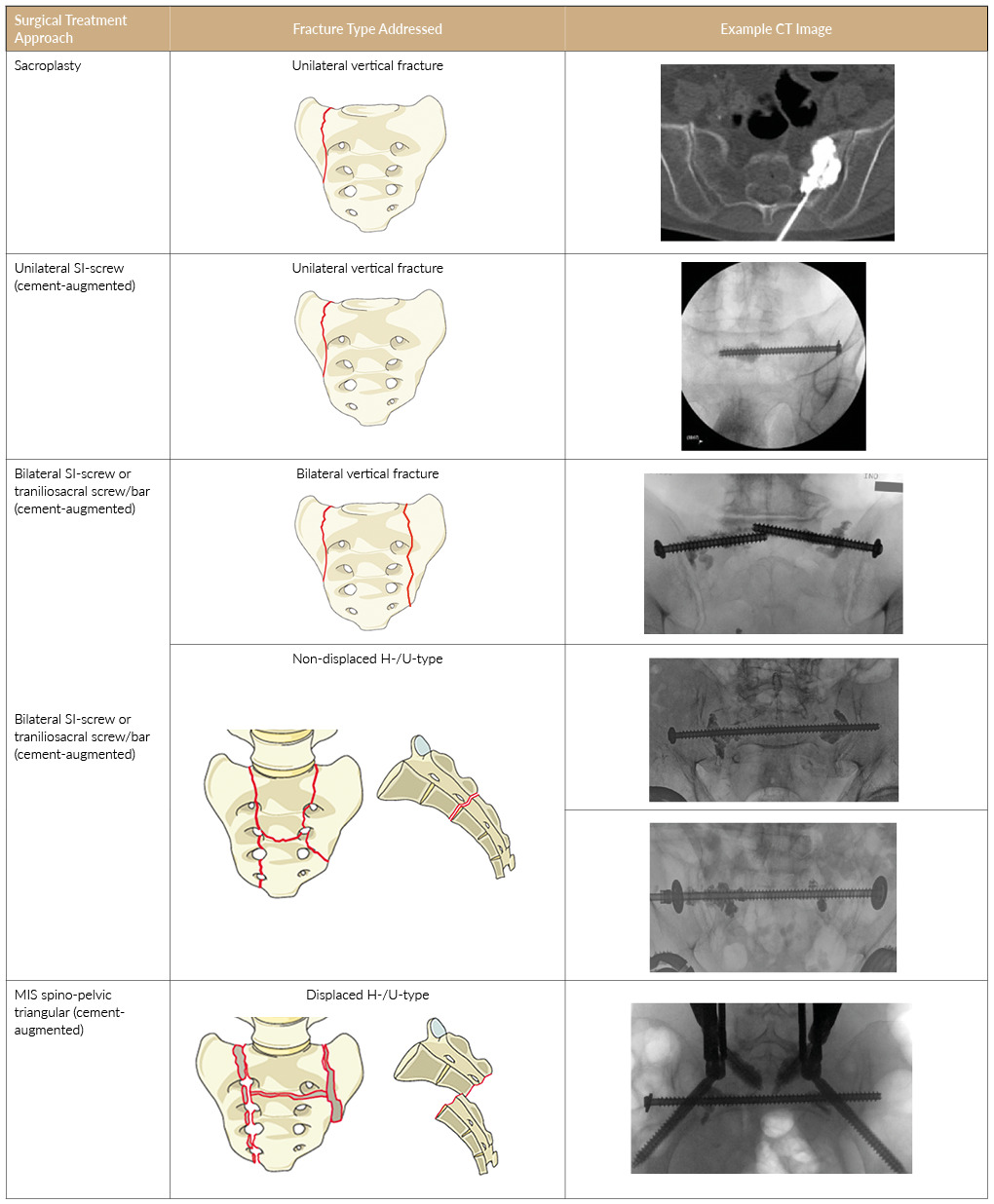

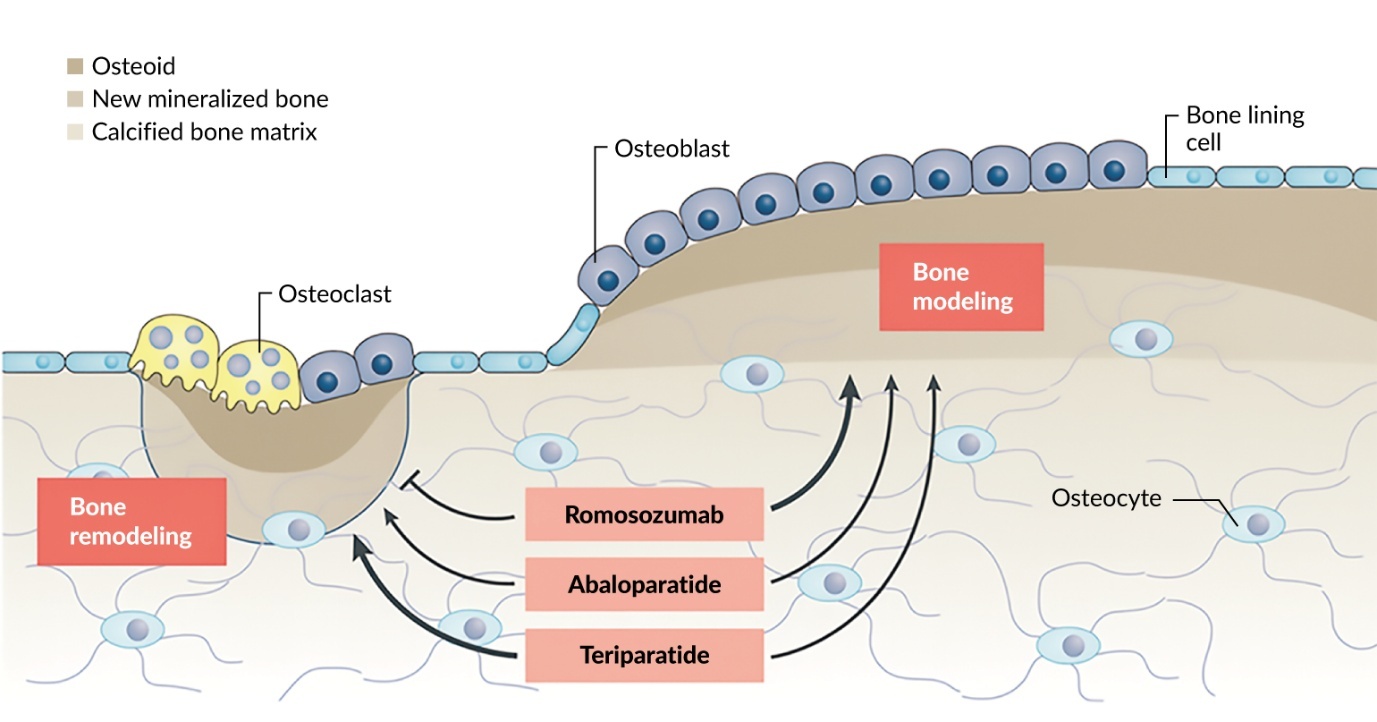

Treatment strategies for osteoporosis include anabolic and antiresorptive therapies, each targeting different pathways in bone metabolism to optimize bone health and reduce fracture risks (Figure 1).16,17 Anabolic treatments, such as parathyroid hormone (PTH) analogs (e.g., teriparatide and abaloparatide), stimulate bone formation by activating osteoblasts, effectively building new bone and increasing BMD.17 These therapies are particularly effective during a defined ‘anabolic window,’ where bone formation exceeds resorption.17 For patients with very high fracture risk, anabolic treatments should be prioritized as the first-line therapy. This is especially important for individuals who have sustained fractures, as these therapies are designed to rebuild bone more effectively in such high-risk scenarios.16,17

Antiresorptive treatments, including bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronate and alendronate) and RANK ligand monoclonal antibodies (e.g., denosumab), work by inhibiting osteoclast activity, thereby slowing bone resorption and maintaining existing bone mass.18 Romosozumab, a sclerostin antibody, offers a unique dual mechanism of action by simultaneously promoting bone formation and reducing bone resorption, making it a highly effective option, especially for patients at high risk of vertebral fractures.16 Clinical trials have demonstrated that therapies like romosozumab yield sustained decreases in fracture rates, even after transitioning to antiresorptive treatments such as denosumab or bisphosphonates.19,20 However, these treatments require careful long-term management to prevent rebound effects, as discontinuation of drugs like denosumab can lead to severe vertebral fractures unless followed by bisphosphonates.19 Furthermore, all antiresorptive therapies are associated with potential rare risks, including osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures, emphasizing the importance of individualized treatment plans and extended dosing intervals where appropriate to minimize these complications.19

Customizing treatment plans with a balance of efficacy and safety is crucial, integrating adequate calcium, vitamin D and protein alongside physical activity. Ensuring sufficient physical activity not only improves bone health but also mitigates risks associated with falls and fractures. Regular consideration of dietary adequacy, including intake of calcium, vitamin D and protein, further supports overall skeletal health and therapeutic outcomes.5 For very high fracture-risk patients, such as post-fracture individuals aged over 50 years, therapy sequences should follow a strategic approach, initiating anabolic treatments before moving to antiresorptive options.21

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to osteoporosis treatment, as management plans must be tailored to each patient’s unique needs.22 Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of evidence-based antiresorptive and anabolic therapies for osteoporosis management.

Primary and secondary prevention strategies

Within the context of osteoporosis management, it is critical to distinguish between primary prevention, which focuses on maintaining bone health and preventing the onset of osteoporosis and fractures, and secondary prevention, which aims to reduce the risk of subsequent fractures in individuals already diagnosed with osteoporosis or who have sustained a fragility fracture.23

A related yet often underappreciated area is the distinction between fragility fracture prevention and the prevention of mechanical complications in osteoporotic patients undergoing or following spine surgery.24–26 While standard fragility fracture prevention centers on systemic bone health and fall risk reduction, management in the surgical context must also address factors specific to operative intervention.25 This includes preoperative bone quality optimization, selection of surgical constructs tailored to poor bone stock, and vigilant postoperative monitoring to minimize implant-related complications.25,26

For example, a retrospective study by Anderson et al. (2020) evaluated bone health in 104 elective spine surgery patients.26 Most were older women with risk factors such as prior fractures and chronic conditions. BMD was measured at multiple sites, and fracture risk was assessed using FRAX with and without BMD and trabecular bone score (TBS). Based on these assessments, pharmaceutical treatments were recommended for 72% of patients, including anabolic agents (42%) like teriparatide and abaloparatide to stimulate new bone formation and improve bone strength, and antiresorptive agents (30%) like bisphosphonates and denosumab to stabilize bone density, with treatment initiated at least three months before surgery to optimize bone quality and minimize surgical risk.26

Transitioning between pharmacological and long-term therapy considerations

The 2020 Swiss Association against Osteoporosis (SVGO) recommendations outline a risk-based approach to osteoporosis treatment, categorizing patients into four levels: imminent/very high, high, moderate, and low.22 Imminent/very high-risk patients, such as those with recent major fractures, face a high refracture risk (40–60% within two years) and should start with anabolic therapies like teriparatide or romosozumab, followed by antiresorptive agents (e.g., zoledronic acid or denosumab) to maintain bone density gains.22,27 These therapies are typically limited to 12–24 months, after which transitioning to an antiresorptive agent is essential to reduce rebound risk.20,28–31 Transition strategies should be guided by monitoring BMD) and bone turnover markers (CTX, P1NP) to ensure effective timing and efficacy.22,32 High-risk patients, including those with older fractures or on glucocorticoids, are advised to use potent antiresorptives as first-line treatments, with teriparatide as an alternative for severe cases.22 Moderate-risk patients, such as those with osteopenia or low BMD without additional risk factors, may benefit from selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERMs) or oral bisphosphonates, particularly if bone turnover markers are elevated.22

Long-term therapy considerations include the use of bisphosphonates for 3–5 years with a possible “drug holiday” for low-risk patients, while denosumab requires continuous use or a planned transition to a potent bisphosphonate to prevent rebound bone loss and vertebral fractures.28,33,34 Regular monitoring of BMD, fracture history, and biochemical markers is critical to optimize treatment outcomes and ensure long-term safety and efficacy.28 Figure 2 illustrates the SVOG tailored and sequential strategies to optimize fracture prevention and long-term outcomes.22

Fragility fracture morphology and classification

The Rommens43 and OF-Pelvic44 classifications are two pivotal systems for categorizing pelvic fractures, each with distinct focuses and approaches. Together, these classifications provide complementary insights into fracture management, balancing stability-focused categorization with a holistic, score-driven evaluation. Both systems are specifically designed to address fragility fractures.

The Rommens classification emphasizes fracture stability and morphology, categorizing fractures into four main types with increasing instability from type 1 to type 4.43 Type 1 (20% of cases) involves isolated anterior pelvic ring fractures, treated conservatively, while type 4 (20% cases) represents bilateral displaced posterior pelvic ring fractures, the most unstable, often requiring direct surgery. Type 2, the most common (50% of cases), includes non-displaced posterior fractures and may need surgery if pain or mobilization issues persist, while type 3 (10% of cases) involves unilateral displaced posterior fractures.43

Notably, up to 80% of these fractures may require surgical intervention.45 Unlike classifications for non-fragility fractures, which prioritize mechanical forces and trauma mechanisms, the Rommens system focuses on the unique challenges posed by weakened bone structures. However, it does not predict clinical outcomes. Instead, treatment success is defined by pain reduction and early mobilization, emphasizing the need to tailor treatment plans to individual patient needs rather than relying solely on classification systems. Surgical success is measured by reduced pain, improved mobility and enhanced quality of life. For younger patients, more aggressive treatments may be necessary to maintain alignment and mobility, while for elderly patients, the focus is often on pain relief and improving quality of life.

In contrast, the OF-Pelvic classification offers a more comprehensive, score-based system that integrates imaging (CT/MRI) and clinical factors.44 It categorizes fractures into five groups based on patterns, includes three modifiers and incorporates additional clinical considerations such as mobilization, pain and neurological status (Figure 3).44 Points are assigned for each category, with scores above 8 typically indicating the need for surgery. This system is specifically tailored to fragility fractures, addressing the unique challenges of low-energy trauma and the progressive nature of osteoporotic injuries. Unlike systems for non-fragility fractures, which often focus solely on fracture morphology, the OF-Pelvic classification incorporates patient-specific factors such as bone density, pain severity and functional status, making it a valuable tool for guiding treatment in elderly and osteoporotic populations. Fracture progression occurs in 40% of cases, predominantly in females, with high pelvic incidence as an independent risk factor.44,45

Referral criteria for surgical evaluation

Non-traumatic or insufficiency fractures, particularly in the spine and pelvis, often require a multidisciplinary approach to optimize outcomes. Surgical evaluation should be considered in cases where conservative management is insufficient or when specific clinical criteria are met. Table 2 provides an overview of the key criteria to consider for surgical referral. By incorporating these criteria into clinical practice, non-surgical clinicians can identify patients who may benefit from timely surgical intervention, ensuring optimal outcomes.43,46

Osteoporotic vertebral fractures

Guiding treatment decisions with the OF scoring system

The OF scoring system plays a critical role in classifying vertebral body involvement and guiding treatment decisions for osteoporotic vertebral fractures.46 This system evaluates the severity of the fracture, ranging from minimal deformity to severe collapse, by assessing key parameters such as the degree of deformity, presence of bone marrow edema and involvement of the posterior wall.46 Organized into five groups, the OF classification ranges from OF1, indicating no vertebral deformation, to OF5, which relates to injuries involving distraction or rotation, and has demonstrated substantial interobserver reliability (Figure 4).

Alongside these morphological factors, the classification score incorporates additional criteria, including overall bone density, progression of kyphosis, patient pain levels, neurological impairment, mobility and general health status.46 The resulting score guides clinical decisions, with a score above six typically necessitating surgical intervention, while a score of four suggests suitability for conservative treatment. Despite its utility, the system is not without limitations, as it omits considerations such as patient age, which can significantly influence treatment outcomes. For instance, the same fracture might warrant different approaches based on whether the patient is relatively young or elderly. This underscores the importance of integrating the scoring system with individual clinical judgment to tailor interventions effectively and improve patient outcomes. These principles are consistent with current guidelines of the Swiss Society of Spinal Surgery for the surgical management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures.50

Surgical techniques for vertebral fractures

Cement augmentation procedures, such as vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, are commonly considered for osteoporotic and fatigue spine fractures, particularly in patients with vertebral compression fractures (VCFs). It is notable that 25% of women over the age of 50 experience at least one VCF, with this prevalence increasing to 50% by age 80, leading to approximately 3.6 million VCF cases annually in the EU.2,52 However, not all fractures necessitate surgical intervention, as many occur and heal unnoticed or can be managed successfully with conservative treatments such as physical therapy and pain management.48,53 The decision to intervene surgically hinges on careful evaluation of the patient’s condition. Indications for cement augmentation typically include severe acute pain, lasting or chronic pain, significant vertebral deformity, or progressive kyphosis that affects the patient’s quality of life.47 For these subgroups with more serious impairments, selecting the appropriate procedure for each case is critical to achieve pain relief, improve spinal stability and prevent further deterioration. The clinical approach should always be personalized, ensuring that only patients who will truly benefit from such interventions receive them.

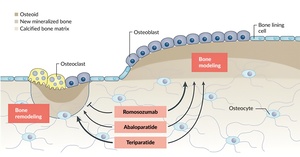

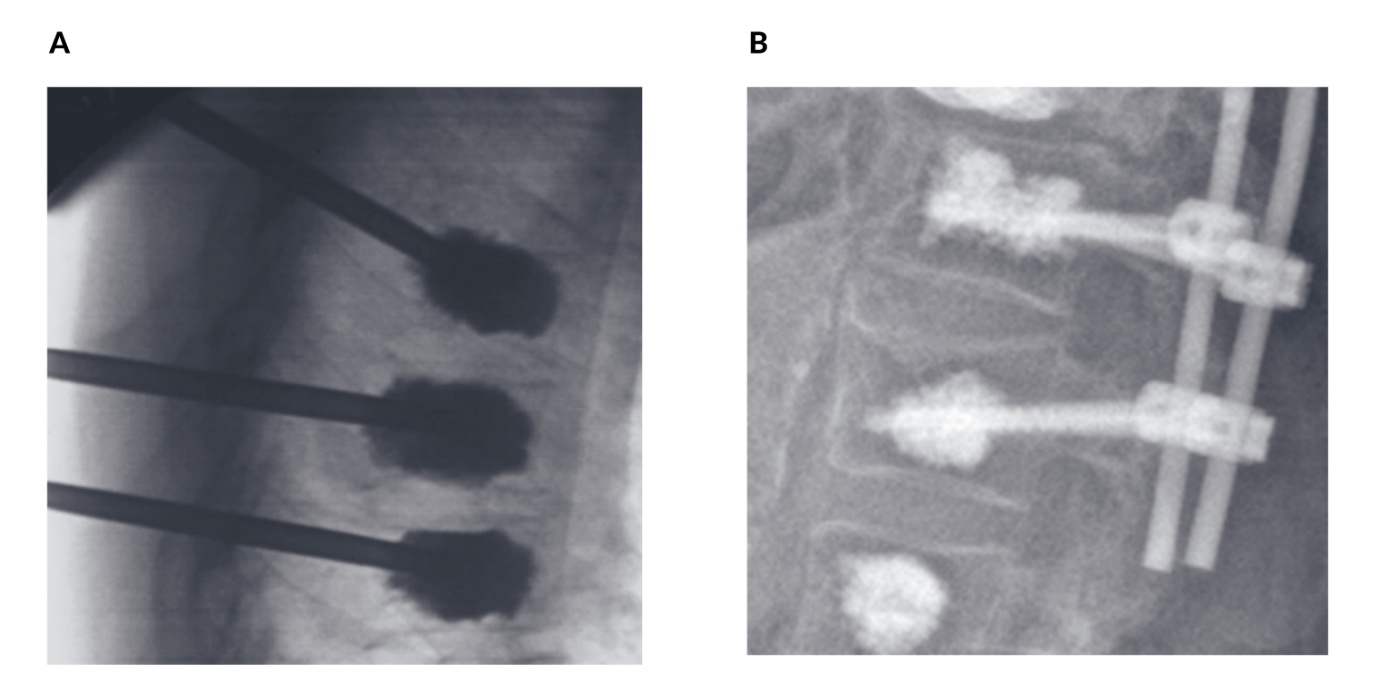

For patients suffering from painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures, surgical options such as vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty offer effective solutions.48,51,53 Vertebroplasty is a minimally invasive procedure where polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement is injected directly into the fractured vertebra to stabilize it and alleviate pain (Figure 5A). Kyphoplasty, an extension of this technique, involves inserting a balloon into the vertebral body before the cement is injected, allowing for the restoration of vertebral height in cases of severe collapse. These approaches can be further enhanced with posterior fixation techniques, which provide additional stability, or with pedicle screw augmentation using PMMA cement (Figure 5B).

Risks of vertebral augmentation procedures

Although effective in treating osteoporotic vertebral fractures, augmentation procedures come with inherent risks. Cement leakage is one of the most critical complications, as it can enter the spinal canal or foramen, potentially causing severe neurological issues, including paraplegia, or pose cardiovascular risks due to cement or fat emboli.54 An important manifestation of venous cement leakage is pulmonary cement embolism. Pulmonary cement emboli are reported in approximately 2–26% of vertebral augmentation procedures,55 although the vast majority of these events remain clinically asymptomatic and are detected only on imaging. Nevertheless, new-onset respiratory symptoms or hemodynamic compromise after vertebral augmentation warrant prompt evaluation to exclude clinically relevant cement pulmonary embolism.

Adjacent vertebral fractures are another concern, occurring in approximately 11% of cases within two years, often influenced by factors such as low bone density, diabetes and local kyphosis.54,56,57 Neurological deficits, though less common (0.32% incidence), may arise from misplacement of instruments or cement leakage.58 These risks demonstrate the importance of precise technique, careful risk assessment and individualized treatment planning to minimize complications and improve patient outcomes.

While vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty remain the gold standards for treating vertebral fractures, new augmentation technologies, such as strut-supported cement techniques, are being developed.59 These emerging technologies aim to enhance biomechanical stability, but their efficacy is still under evaluation.

Sacral fatigue fractures

Sacral fractures are a significant yet often underdiagnosed aspect of osteoporotic fractures, affecting up to 7% of cases involving the sacrum or pelvis.60 These fractures can have a profound impact on patients, with a loss of independence reported in nearly 90% of cases61 and a one-year mortality rate ranging between 13% and 27%.62–65 Risk factors for sacral fractures overlap with those of other osteoporotic injuries, including primary and secondary osteoporosis, tumors, radiotherapy and physiological conditions such as pregnancy or lactation.66–69 Unique risks include a high pelvic incidence, previous spinal instrumentation extending to S1 without involving the pelvis and degenerative spondylolisthesis at the L5-S1 level.

Diagnosing sacral fractures can be challenging due to vague symptoms such as lower back pain or, less commonly, groin pain, which often delay identification. A low-energy trauma history is present in only one-third of patients,70 and sacral fractures accompany up to 98% of anterior pelvic ring fractures,45 making thorough evaluation essential. Imaging plays a critical role in diagnosis; conventional X-rays have a sensitivity of just 20-34%,45,68,70,71 CT scans offer improvements with sensitivity up to 75%,45,71–73 but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the gold standard with 99% sensitivity.68,72

Spinopelvic dissociation fractures

Spinopelvic dissociation fractures, often referred to as U&H fractures, are a rare but severe subtype of pelvic injuries characterized by a distinct and complex fracture pattern. These injuries feature bilateral vertical fracture lines combined with a horizontal fracture line, forming a U- or H-shaped configuration (Figure 6).45,74 This unique pattern is associated with a rupture of the spinopelvic ligaments, which are crucial for maintaining the structural stability of the pelvis and its connection to the spine. The disruption of these ligaments further exacerbates the instability of the fracture, making it particularly challenging to manage. One of the critical considerations in spinopelvic dissociation is the necessity of surgical intervention. Studies have shown that attempting to treat these fractures conservatively results in a 100% failure rate due to the severe instability and inability of the ligaments and bone to heal adequately without mechanical support.74 Consequently, surgical stabilization is universally recommended for U&H fractures.74 Surgery aims to restore stability to the pelvis, realign the fracture segments and secure the disrupted ligaments, thereby improving the structural integrity of the spinopelvic junction and facilitating functional recovery.45,74

Fragility fractures of the pelvis

Spinopelvic dissociation fractures are often discussed in the broader context of fragility fractures of the pelvis, particularly in populations susceptible to bone density loss, such as older adults, especially females. Fragility fractures occur due to low-energy mechanisms, such as falls, and highlight underlying skeletal fragility, often linked to osteoporosis. Among these, sacral insufficiency fractures or pelvic ring injuries are frequently observed. Fracture progression is a notable concern, occurring in approximately 14% of fragility fractures of the pelvis.75 This progression is most commonly seen in female patients and is significantly influenced by anatomical factors, such as a high pelvic incidence.75 A high pelvic incidence refers to the angulation of the pelvis and spine; when excessively pronounced, it can increase mechanical strain on the pelvis, raising the likelihood of fracture progression.

Management of sacral fatigue fractures

Pelvic fractures, particularly fragility fractures and complex patterns like spinopelvic dissociation, present substantial challenges in treatment, especially in frail patients.45 These individuals often have significant comorbidities, such as osteoporosis or chronic illnesses, which compound their vulnerability.45 Immobilizing pain not only affects their quality of life but also imposes risks of complications from prolonged inactivity, including infections, pressure ulcers, venous thromboembolism and muscle atrophy.45 Given these challenges, the primary goals in treatment are achieving rapid pain reduction, enabling early mobilization and selecting minimally invasive methods to minimize surgical risks and promote faster recovery.45

The initial management for sacral fatigue fractures is often conservative and symptom-oriented, focusing on adequate analgesia, protected weight-bearing and guided mobilization or physiotherapy. In many patients, pain and mobility improve under such measures and invasive procedures are not required; therefore, the decision to escalate to sacroplasty or screw fixation should be based on persistent immobilizing pain and functional restriction. A carefully monitored conservative treatment over days to a few weeks can help avoid unnecessary surgical risks, especially in multimorbid and frail patients.

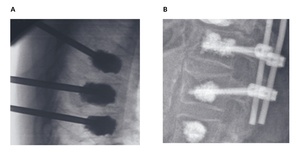

Minimally invasive techniques and surgical options play an important role in the management of sacral fatigue fractures (Figure 7). Sacroplasty, which involves injecting PMMA cement into the sacrum, is one of the less invasive methods aimed at reducing micromotion and achieving thermal pain relief.76 Although sacroplasty has shown up to 80% pain reduction within two weeks and 90% within a year,77 its utility for improving stability remains controversial.78,79 The risks of cement leakage into surrounding structures, such as the spinal canal, can lead to neurological complications affecting the L5 and S1 nerve roots and in some cases, the procedure alone is insufficient for unstable fractures, as seen in U- or H-type fractures.76,80

Sacroiliac screw fixation is another widely used minimally invasive intervention, offering mechanical stabilization for unstable pelvic fractures.81 This technique often involves image-guided or navigated percutaneous screw placement, which is particularly advantageous in frail patients with osteoporotic bones.81 Bilateral or transiliosacral screw configurations with or without cement augmentation are common approaches. Cement augmentation, specifically using PMMA, has been demonstrated to enhance pull-out strength by 2.2 times, making it beneficial in cases with severely compromised bone quality.82 However, precise preoperative imaging and planning are crucial to ensure safe screw placement, as complications arising from malpositioning, including vascular or neural injuries, have been reported. Other issues, such as screw loosening (17%), migration, or failure of fixation,83,84 can occur, emphasizing the importance of meticulous surgical technique and preoperative assessment, including CT scans to map anatomical variations and identify safe screw corridors.

For complex patterns, such as spinopelvic dissociation fractures, spinopelvic triangular stabilization is considered the gold standard.49 This approach involves the use of spinal instrumentation from L5 to the ilium, combined with sacroiliac screws and, in some cases, cement augmentation. Triangular stabilization has been shown to provide superior biomechanical properties, addressing both vertical and rotational instability.49 This technique is particularly effective for severe U- or H-type fractures where the structural integrity of the entire spinopelvic unit is compromised. While this approach offers robust stabilization, it can be technically demanding, requiring advanced surgical expertise and careful patient selection to reduce perioperative risks.49

Conclusions

Osteoporosis, especially its effects on the spine, presents a major public health challenge closely associated with aging. This condition not only weakens bones and causes vertebral fractures but also has profound psychological and socioeconomic consequences. Early detection is important, with regular screenings using advanced tools such as DEXA together with FRAX to identify individuals at risk and enable timely interventions. Treatment plans should be personalized according to individual risk profiles, prioritizing anabolic therapies for high-risk patients and transitioning to antiresorptive treatments for long-term management. Lifestyle modifications, such as ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, engaging in weight-bearing exercises and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, are essential for supporting bone health.

Across the spectrum of osteoporotic fractures, conservative and functional treatment remains the cornerstone of care. Optimized analgesia, early mobilization, fall-prevention strategies and structured rehabilitation, together with appropriate pharmacological osteoporosis therapy, should be prioritized and fully exploited whenever feasible. Surgical interventions should be reserved for clearly defined indications, such as unstable fracture patterns, progressive deformity or persistent, disabling pain despite comprehensive conservative management. Nevertheless, surgical interventions play a vital role in managing complex osteoporotic fractures, particularly in cases where conservative treatments fail or fractures significantly impair the quality of life. Minimally invasive procedures, such as vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, provide effective pain relief and restore spinal stability in patients with vertebral compression fractures. For more complex cases, such as sacral fatigue fractures or spinopelvic dissociation, advanced surgical techniques like sacroplasty and spinopelvic triangular stabilization are essential to restore function and stability.

Interdisciplinary care is equally important, fostering collaboration among healthcare providers, including endocrinologists, orthopedic surgeons, and physical therapists, to deliver comprehensive and effective treatment. Additionally, raising public and clinical awareness of osteoporosis can help reduce stigma, improve adherence to treatment and prevent fractures. By integrating these strategies, including both pharmacological and surgical approaches, healthcare providers can significantly alleviate the burden of osteoporosis, enhancing mobility, independence, and quality of life for affected individuals.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written consent for the further use of patient data was obtained.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained.

Availability of data and materials

All patient data are included in the anonymized form in the published article.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that the manuscript was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

_treatment_recommendations_by_risk_level.png)

-pelvis_classification_system._localization_of_edema_in_of1.png)

.png)

.png)

_treatment_recommendations_by_risk_level.png)

-pelvis_classification_system._localization_of_edema_in_of1.png)

.png)

.png)